Much of the following article is based on a 2024 biography of Frank Masland Jr. entitled A Conservative Environmentalist: The Life and Career of Frank Masland Jr., Pennsylvania State University Press, 2024, by Thomas G. Smith, professor emeritus of history at Nichols College in Massachusetts. I found this book to be engaging from start to finish. Other sources for the article include the Dickinson historical archives and Cumberland County Historical Society.

Frank Masland was one of the giants in the American environmental movement of the mid-20th century, influencing national parks in America and around the world. His career in American industry, his passion for nature and adventure, and his service to the federal government as an advisor to US Department of Interior, not to mention his work with Pennsylvania’s Department of Natural Resources, all point to a man with an unusually large scope of accomplishments.

Timeline of Frank Masland Jr’s life: See an overview of Masland’s amazing scope of activities and accomplishments.

Note: All photos are courtesy of the Dickinson College Archives & Special Collections, Carlisle, Pennsylvania, except those that are credited to Masland.org.

____________________________________________________

Overview

Frank Masland Jr. was an unusual mixture: Equal parts David Attenborough, Henry Ford, and John Bircher. As an industrialist who loved nature, he also embraced ultraconservative politics. He’s been called an environmentalist before there was an environmental movement. In the 1940s and 1950s, he realized that rampant consumerism, limited natural resources, and delicate ecosystems were on a collision course that imperiled the future of humanity. He spent the remainder of his life trying to convince people that preservation of nature was vitally important.

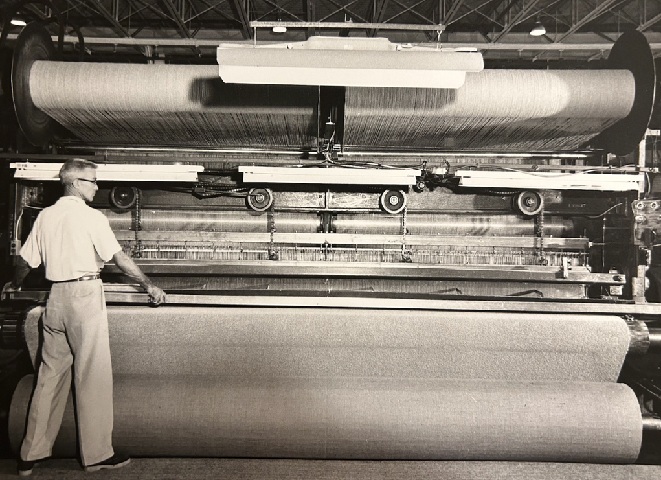

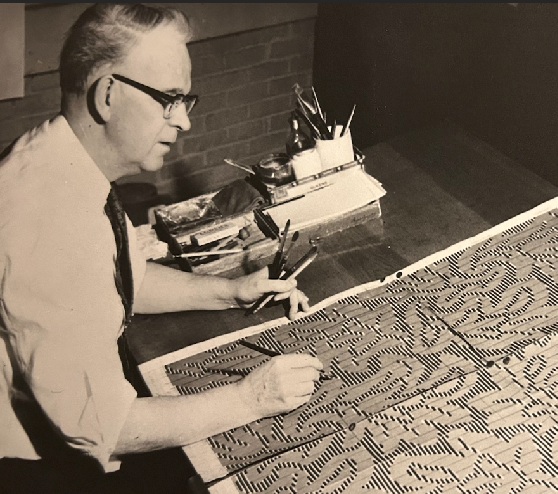

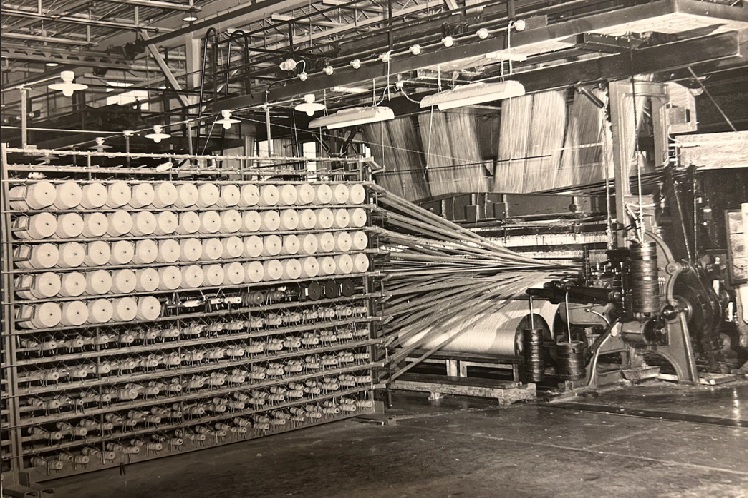

Masland was born into a family of weavers that traced its origins back to Nottinghamshire, England of the 1700s. Two Masland brothers moved to America in the 1830s, where they set up shop in Massachusetts. They eventually moved their weaving operation to Philadelphia, where Frank Masland Jr. was born in 1895. Frank attended Dickinson College in Carlisle, PA, then served in the US Navy during WWI. Afterwards he joined the family business just in time for the Roaring 20s, the Great Depression, and WWII.

The Masland company became one of the nation’s leading carpet manufacturers, particularly during WWII, when government contracts were rolling in. After the war, Frank chose early retirement, dedicating his time to exploring remote parts of America and serving nearly three decades as a member of the National Parks Advisory Board. Though he was well-known among other conservationists during his time, today he is largely forgotten despite having been “involved in nearly every major environmental issue in the post-WWII era,” according to biographer Thomas Smith.

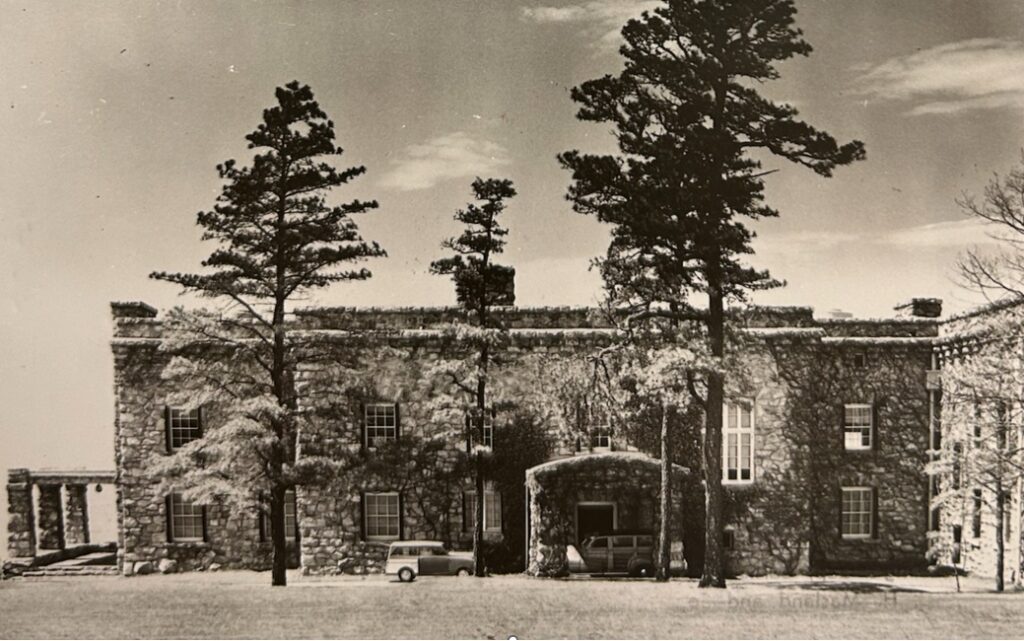

In 1951 Frank Masland Jr. had been semiretired only a few years when he purchased Kings Gap from the estate of James McCormick Cameron, who began construction of the mansion in 1908. The purchase included a 1,200-acre forest, a 32-room mansion with a breathtaking view of the Cumberland Valley, and a large carriage house with servants quarters. Masland used the property mostly as a company retreat and meeting spot for guests related to his work with the National Park Service.

Frank’s influence as an advisor to the national park system peaked in the Kennedy and Johnson administrations when he became Interior Secretary Stuart Udall’s right-hand man, performing all manner of special assignments. He scouted out new parks, traveled to third-world countries to help set up national park systems, and helped establish land-use policies that balanced the needs of native Americans, ranchers, hunters, miners, loggers, hikers, and urban populations.

While environmental causes were receiving bi-partisan support when Frank first became an advisor in the 1950s, a trend which continued into the 1960s-1970s, he was rudely awakened by what some historians have called the “Republican reversal” under Ronald Reagan. First, Reagan appointed his campaign manager as Park Service Director, then he appointed James Watt as Interior Secretary, possibly as a favor to beer baron Joseph Coors, a major Republican donor. For decades, people like Teddy Roosevelt, John Muir, Gifford Pinchot and others had worked hard to establish the first national parks and protect other federal lands from development. Over time, this only angered many westerners, who perceived that Eastern environmentalists were trying to “preserve the open horizons of the American West as their own personal playground,” according to James Watt.

Joseph Coors created the Mountain States Legal Foundation (MSLF) in 1976, with James Watt as its first president. Their sole purpose was to “protect the rights of westerners to access public resources in their region.” Joseph Coors and Frank Masland had much in common: conservative industrialists who inherited a family business, with anti-union, anti-statist, and deeply religious views. But the two of them couldn’t have been further apart when it came to developing and preserving federal lands.

Masland was above all a “preservationist,” as opposed to merely a “conservationist.” A conservationist advocates for a “wise use” policy that offers some protection to nature but also includes amenities for people such as beaches, hotels, trails and campgrounds. As a preservationist, Masland sought to minimize roads, dams, and other human interventions. Some considered this viewpoint elitist. However, for Masland, his experience with nature was bound up with his religious faith. He believed deeply in the power of nature to connect us with our divine creator and heal our troubled world. Masland was ultra-conservative politically, but his views on the environment were on the far end of the spectrum, in visionary territory. To him, preserving nature was necessary both for the survival of the planet and the human species. (See Masland the visionary ahead.)

By the early 1970s, Frank was in his mid-70s, no longer taking strenuous rafting journeys or pack expeditions through canyon country. He seems to have been less interested in Kings Gap as well. The Masland company’s general manager attempted to sell the property to a developer who planned to build 400 homes and a golf course. As chairman emeritus of the board of trustees, Frank strongly objected and was tasked with selling the property himself. He tried to donate it to the National Park Service as a tax-free gift valued at $1 million, but the Park Service declined, stating the facility was too small for their needs. Frank then came up with a plan to sell the property to the Nature Conservancy for $400,000, then gift them with a charitable grant of $400,000 so they could donate the property to the state of Pennsylvania. This what happened. Why such a complicated deal? Perhaps Frank felt this would best guarantee the land would be preserved.

Frank successfully appealed to the state not to harvest the trees and to continue his annual outdoor Easter church service, rain or shine (or snow!). Kings Gap officially became a State Park, with a mission to conserve the land for future generations. Kings Gap also has the distinction of being an Environmental Education Center, one of only four with this designation among Pennsylvania’s 124 parks. Environmental education was near and dear to Masland, and is now the primary goal at Kings Gap, which offers a variety of public programs, school student curriculum, and professional development for educators.

Frank’s Background

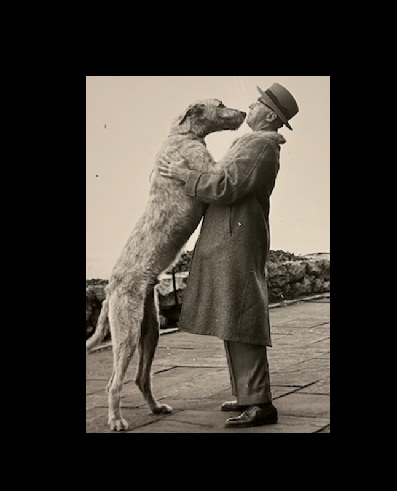

Who was this man Frank Masland and what were the main influences that shaped him? Frank Masland Jr. was born in 1895 in the Kensington area of Philadelphia, not far from his family’s carpet mill in the mill district. (Today Kensington rivals San Francisco as having one of the nation’s worst homeless and drug addiction districts.) When Frank was a year old, his family moved from Kensington to the small community of Bustleton northeast of Philly. Their 23-room mansion on 14 acres was staffed by two maids, a horse trainer, a gardener, a coachman, and later a chauffeur. It also featured a stable full of Frank Senior’s 30 racehorses. Frank Jr. roamed the fields and forests to his heart’s content, catching frogs and turtles, riding ponies, and playing with their Saint Bernard. Theirs was an evangelical Methodist family, which meant card playing, theater going, dancing, and drinking were considered sinful.

The Masland family rarely vacationed but Frank Jr. got to spend two months a year at a private summer camp in Maine from age ten to eighteen, where his passion for the outdoors grew even stronger. That passion did not carry over to his studies, however. While he played sports in high school, his school yearbook recorded that his goal was simply “to graduate,” his chief characteristic was “laziness,” and his favorite activity was “going to Philadelphia.”

While Frank’s family life may have seemed idyllic from the outside, it was not without its issues. His father lived large, indulging in drink, racehorses, automobiles, and country clubs. Frank’s parents divorced in the 1920s, with Frank Sr. eventually taking up with one of the maids and moving to Florida. Frank Sr.’s excesses only reinforced Frank Jr.’s abhorrence of philandering, divorce, burlesque, abortion, and crude jokes.

In 1914, Frank Jr. entered Dickinson College in Carlisle, the town where he would remain for the remainder of his long life. (He died in 1994 at age 98, still living in the Cumberland Co. home he purchased in the 1930s.) Masland enjoyed playing football and attending co-ed functions in college, but his academic performance was once again less than stellar. Born into wealth and privilege, he knew his future lay in going to work for the family business. Nor was he all that interested in politics or the topics of the day, such as prohibition, the war in Europe, or women’s suffrage. He did show a penchant for getting into mischief, however. The Smith Biography documents some of his pranks: Hidden alarm clocks set to disrupt chapel services, a professor’s automobile stripped of wheels and physically carried to another location, or a bicycle dangled from a campus statue. While at college, he managed to find the love of his life, Virginia Sharp, sister of a fraternity brother. He remained faithful to her for the remainder of their lives (she predeceased him in 1984).

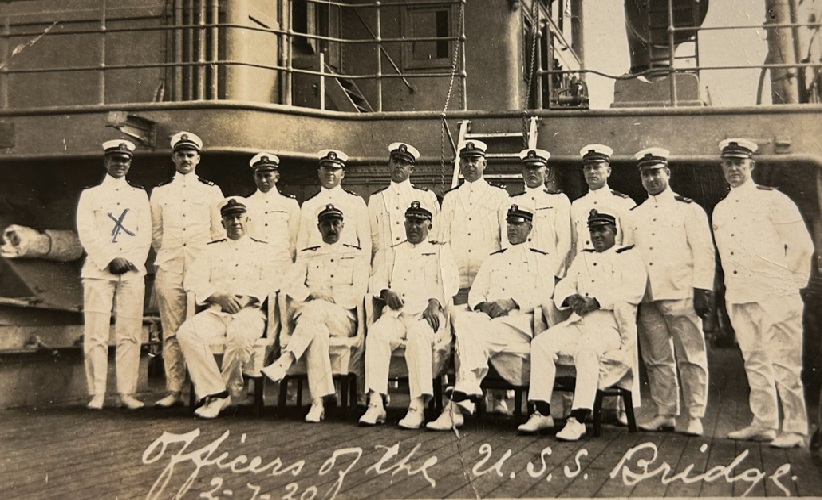

Masland entered Dickinson Law School in 1916 but dropped out after a year to join the armed forces. Four million young men followed suit, swayed by Woodrow Wilson’s desire to “make the world safe for democracy.” Although the Great War started in 1914, the US wouldn’t enter till 1917. Masland joined the Navy and was first assigned to patrol the Atlantic in the family’s 57-foot yacht, leased to the Navy for one dollar per month. With his father’s help he was promoted to commander on an M 246 submarine chaser patrolling the mid-Atlantic coast. Frank married Virginia while on leave in 1918. At war’s end he joined the Reserves and began his career at Masland and Sons.

In 1919 Frank was tasked with overseeing the relocation of the Masland mill to Carlisle, during the flu epidemic of 1918-1919. At its peak, the epidemic was killing 5,000 Philadelphians per week. In Cumberland County, the virus killed about 1% of the population, 275 people in total. The Carlisle Indian School was closed and converted into the US Army Medical Center to treat flu victims. Stores, bowling alleys, and saloons were required to cut back hours or close for a time, not unlike the Covid epidemic of 2020-21.

Masland became general manager of the Masland company in the 1920s, which had grown into one of the world’s largest carpet manufacturers. Although Frank and his other family members were adamantly against all unions, the Masland company was quite generous with its benefits package, which included a group insurance plan, several sports leagues, an annual picnic at Hershey Park as a paid holiday, a company newsletter, and also the first two days of hunting season as paid holidays. The benefits would expand to include profit sharing, a subsidized health and hospital plan, and a college fund for children of employees. While labor unrest struck the auto and steel industries in the 1930s-40s, the Masland mill was “tranquil,” according to biographer Smith.

The Great Depression hit the Maslands hard. Frank Sr. lost most of his fortune. Carpet mills across the country lost more than half of their business. The Masland mill was losing money but hung on by a thread (pun intended). In 1930 Frank Jr. was nominated president of the company at age 36. He reduced company operations to 30% of capacity and cut work hours. By 1932, unemployment would reach 30% in Carlisle.

In 1934 Frank purchased a 300-acre farm on Old York Road outside of Carlisle. The property featured dense forest, open fields, and two bodies of water: the Yellow Breaches and Mountain Creek. The home was in disrepair, however. Its roof sank to the basement, such that the house was dubbed “Fallen Arches.” Frank, his wife Virginia, and their two boys slept in the barn while contractors restored the property to its former glory. This would be Frank and Virginia’s home for the remainder of their lives. While Frank ventured off to work and play, Virginia usually stayed at home and ran the farm, which was staffed by locals who raised and butchered the livestock, grew and canned vegetables, churned butter, plucked chickens, and did everything necessary on a subsistence farm.

Like many other wealthy individuals in the 1930s, Frank was not happy with the New Deal, which he believed to be outright Socialism, leading the country to a totalitarian state. The National Association of Manufacturers (NAM), for which Frank would serve as vice-president and director at different times, was also anti-union, pro-business, and conservative leaning. Although unions had been gaining ground for several decades, it was not until President Franklin Delano Roosevelt that labor unions and collective bargaining were suddenly not only tolerated but encouraged. The New Deal also included the National Recovery Act (NRA), which established industrial codes that recognized workers’ rights to organize, a minimum wage, and a maximum work week, along with a brand new National Labor Board to arbitrate disagreements. Other codes aimed at preventing companies from overproducing, unfair competition, and unconstrained layoffs. The US Supreme Court declared the NRA to be unconstitutional, but Congress passed the Wagner Act of 1935 and the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938, essentially granting many of the same rights.

Immediately after the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1943, Masland quickly made the switch to wartime production, making not just canvas and carpets, but also gun barrels and torpedo heads. The number of employees rose from 400 in 1941 to 3,300 two years later, an eight-fold increase. The factory ran three shifts 24/7, producing 80% of all fabricated canvas goods in the US armed forces, including tents, trousers, tarps, and bomber hangars. By 1947, the Masland company was the largest producer of duck cloth in the world.

Despite the Masland company’s huge WWII contracts, their executive salaries were not too far removed from the average worker. While Frank earned $25,000 as company president in 1945, the average Masland employee made $3,000, only an 8.3x multiple. Contrast that with today, when corporate executives typically make 300x multiples of the average worker, or even 600x according to one study. (31st Annual Executive Excess Report on CEO pay.) And in October of 2025, Tesla CEO Elon Musk just received shareholder approval for a $1 trillion annual compensation package!

After the war, the Masland company continued to thrive as demand for carpeting soared in the post-war economy. At this time, Frank took an early retirement of sorts. Unlike many of his contemporaries, he seldom played golf or watched sports or television, preferring instead to spend his free time exploring forests, fields, canyons, and rivers. Frank also became a compulsive letter writer, dictating letters to his personal secretary to be sent to a wide range of recipients, often simply to give them “a piece of his mind.” His prolific output led local newspapers to limit him to one published letter per month.

In April of 1977 he vented to Senator George McGovern, who five years previous had been humiliated in a landslide loss to Richard Nixon:

Dear Sir:

I have been a spectator of the Washington charade for half a century. During that period no one in Government has been a greater threat to our nation's wellbeing than you.

Having been thoroughly and ignominously (sic) repudiated by the electorate, either you yield to a compelling ego or you are possessed by a desire to replace the Republic with a Socialist State. Your constant advocacy of policies of appeasement in our confrontation with the Communist world, your advocacy of concessions, your apparent admiration for those Communist leaders guilty of mass murder implies a sympathy for them, their policies and their form of Government.

If Lenin's prediction that the United States "will fall like a ripe apple" comes to pass, you will have been a leader among those who have brought it about.

Very truly yours,

Frank Masland Jr.

In all fairness, McGovern does not appear to have been quite as extreme as Masland would have us believe. While McGovern was one of the leading opponents of the Vietnam War, he also called out many anti-war protesters as “reckless and irresponsible.” McGovern grew up in poverty but went on to become a decorated WWII veteran, piloting 35 bombing missions over German-occupied lands. After the war he earned a PhD in history and served as a history professor before winning a seat in the US House of Representatives in 1962. He was also a staunch Methodist just like Masland. But unlike Masland, he was heavily pro-union. He also favored a more liberal policy toward the Communist world. For example, he endorsed admitting China into the United Nations. He also joined the Kennedy administration as director of the Food for Peace program. These were all strikes against him in the eyes of Masland, who felt that government should be involved in little more than fighting wars, collecting very limited taxes, and preserving natural lands.

It seems Masland had much in common with Senator Joseph McCarthy, the infamous anti-Communist crusader after whom the “McCarthy Era” is named. During this time (~1947-1956), even a casual association with a communist deep in the past might have ended a person’s political, academic, or entertainment career. According to historian Arthur Schlesinger Jr., Frank was a “hard-line conservative” who defended what Schlesinger called “the old order” that prevailed before the onset of FDR’s New Deal. Today, Frank would probably applaud Project 2025 and other like-minded endeavors that are trying to take us back to the “old order” once again. However, he would probably not stand idly by while many hard-fought environmental protections are being rolled back, similar to what took place under the Reagan reversal.

It’s safe to say hundreds of key political figures of the day received a letter from Frank. He became friends with many of them, including Lady Bird Johnson and Barry Goldwater. Many boxes of these letters are kept at the Dickinson archives. Most of the recipients are unfamiliar to us today, but many still stand out: George H.W. Bush, Jimmy Carter, Bob Dole, Dwight Eisenhower, Gerald Ford, Alexander Haig, John Birch Society founder R.W. Welch, Lyndon Johnson, Henry Kissinger, Tip O’Neill, Dan Quayle, Ronald Reagan, Casper Weinberger, Richard Nixon, Strom Thurmond, to name just a few.

Frank could be vitriolic in his letters, as he was with McGovern, or casual and friendly, as he was with Ralph Nader. He wrote Nader in 1970, acknowledging the two of them were both concerned with conservation, the environment, and pollution. Frank mentions the heavy pollution emitted from trucks, also noting that trucks were not a particular focus of Nader’s. “Trucks are driven today with a total lack of courtesy and with a seeming conviction they possess immunity from arrest,” wrote Frank. Trucks were also hazardous to public safely for the way they often “race each other, tail-gate, jam up traffic, cut in and out and frequently are clocked at 75 miles per hour.” He urged Nader to make trucks one of his “major targets.” It’s hard to reach any conclusion from this letter except that Frank was having fun venting his frustrations to an influential person. The tone was more friendly than not, suggesting that with Frank, environmental causes often trumped political leanings.

Frank joined many nature clubs, including the Explorers Club, the Boone and Crocket Club, Sons of Daniel Boone, Campfire Club, Boy Scouts, Appalachian Mountain Club, Cosmos Club, and Sierra Club. He even carried the Explorers Club flag to remote locations like the American southwest and Antarctica.

In 1946 Frank read a Saturday Evening Post article about a river expedition through the Grand Canyon led by adventurer Norm Nevills. Masland soon booked his first trip with Nevills for July of 1948. For three weeks and 277 miles, Masland negotiated rapids by day and camped on the riverbank by night, in what turned out to be a peak life experience. The grandeur of nature simply overwhelmed him. The trip terminated at the Hoover Dam, but Masland’s journey as an explorer was just beginning. He went on to explore many exciting and dangerous places, including the canyons of the American Southwest, the frigid cold of Antarctica, remote areas of Africa, Panama’s Darien jungle, and the swamps of the Florida Everglades.

Masland’s experience on the rivers and canyon lands of the Southwest gave him an inroad into the federal government. In 1955 he wrote an influential memorandum entitled “Some Thoughts Concerning the Navajo Problem.” In it he made several recommendations: 1) Protect the landscape and Navajo ruins and designate Monument Valley as a national area to be protected by Park Service or Navajo rangers. 2) The San Juan River should be dammed in New Mexico, providing water for irrigation to indigenous peoples in the region. 3) A hydroelectric dam should be built to supply electric power for limited industrial development that could employ tens of thousands of natives, in cooperation with the tribes. Someone in Washington apparently listened. While a few dams were built in this particular region, none were hydroelectric, falling short of Masland’s vision. But his ideas of protecting native lands by designating them as parks and preserves largely came to fruition.

Around this time, the fervor for development was strong. Eisenhower’s Secretary of the Interior, Douglas McKay, was more a proponent of development than he was conservation. He was also a fellow member of the National Association of Manufacturers. Masland lobbied McKay, hoping to win support against any dam project that threatened Masland’s cherished rivers. He invited McKay to Dickinson to receive an honorary degree and to speak. McKay stayed in the Kings Gap mansion during his visit. Masland urged McKay to consider preservation as a priority over development, but to no avail. McKay planned to only increase commercial development on federal land.

As noted, Masland developed a very close relationship with Interior Secretary Stewart Udall during the Kennedy and Johnson years. When Masland’s first six-year term with the National Park Advisory Board ended in 1962, Udall asked Masland to stay on as a special consultant. The two worked together during Udall’s entire eight years at the Department of Interior. One of Masland’s first assignments was to attend the First World Conference on National Parks in Seattle in July of 1962. The conference was designed to help countries around the world develop sanctuaries to protect wild animals and habitat, and parks to promote tourism and economic development. This fit nicely into Kennedy’s Cold War strategy to shore up democracy around the world with the Peace Corps, USAid, and other programs.

The conference was attended by 145 delegates from 63 nations. Masland was particularly impressed by the Africans’ receptivity to the idea of preserving areas of natural splendor, and their aspiration to break free of colonialism. Masland made several trips to Africa, meeting with various countries to help start their national parks programs. Over the next three decades, over 300 new national parks were established around the world, mostly in sub-Saharan Africa.

In 1965 Udall sent Masland on an 11,000-mile two-month trip across the US to assess the health of the national parks and identify threats to their ecosystems. In his reports, Masland criticized the US Army Corps of Engineers for mismanagement of the rivers and dams at the expense of certain endangered species. He also identified poaching and other problems. The fact that Udall entrusted this work to Masland indicates what a special relationship they had. It’s doubtful that this type of partnership would happen today, where a wealthy businessman donates months of his time inspecting and reporting on government business, on his own dime. However, one might argue that this very thing took place with Elon Musk and DOGE in 2024-2025.

Masland the visionary

Time and again Frank was impressed by the Indigenous people he encountered on his journeys. To him, they “possessed many superior features that mainstream white society should emulate,” according to biographer Smith. Masland was conflicted about many aspects of the modern world such as consumerism, which manufacturers like himself had helped create. Masland believed the abundance of televisions, automobiles, and washing machines led to an “overemphasis on materialism,” that came at the expense of spiritual and moral values. Masland was concerned that “man’s seemingly insatiable appetite for things might be destructive to the survival of humankind.”

Masland feared that modern humans were under the illusion they were self-sufficient, apart from nature. As such, he felt humans ran the risk of destroying the ecosystems that support life. While Masland admired indigenous people’s ability to “live in harmony with all creation,” and he established warm friendships with some of his Native American guides, biographer Smith believes Masland still maintained a paternalistic attitude toward them, just as he did his factory workers. During the 1950s when Masland first began encountering Native Americans, the trend in government was still assimilation as the goal. Many of the smaller tribes had already been “terminated,” but the Navajo in particular resisted, in part because their reservation was immense (17 million acres) and their traditions deep (thousands of years). Rather than assimilation, the Navajo, or Dine as they call themselves, wanted self-determination above all. While Masland was sympathetic toward self-determination, he also favored assimilation of medical science and other technologies, provided it did not harm native traditions.

It’s no surprise that Masland resonated with Henry David Thoreau. Masland expressed agreement with Thoreau’s words: “in wildness is the preservation of man.” If wildness is not preserved, wrote Masland, “there will soon come a time when either man will become a robot,” or he will become extinct.

Richard Nixon and the First Earth Day

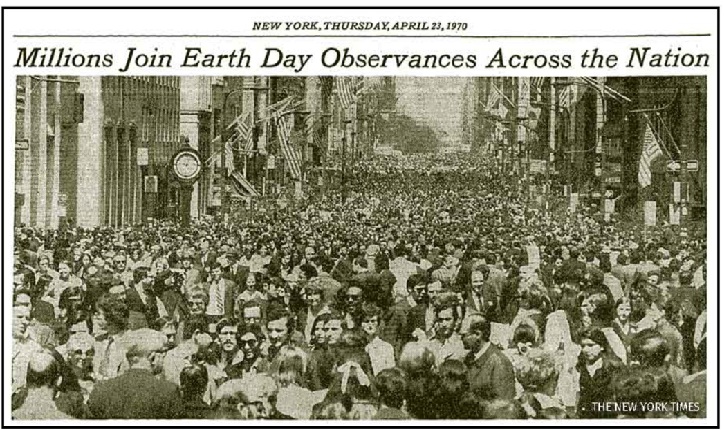

At age 75, Masland was eager to reenter the political arena under the Nixon administration. He made himself available to Nixon’s Citizen’s Advisory Committee on Environmental Quality, but Nixon’s people passed him by. One of Masland’s concerns was that cleaning up pollution would become a substitute for preserving pristine lands. Overall, Nixon’s environmental track record turned out to be quite positive, with the creation of watershed legislation such as the Clean Air Act and Clean Water Act of 1970 and the Endangered Species Act of 1973.

It was during the Nixon era that the first Earth Day took place in 1970. Masland and other conservatives gave their cautious support but were careful to distance themselves from the strong counter-cultural component which was then prevalent. Congress adjourned for the day as speeches and events were held across the nation on the first Earth Day. Many places celebrated not just Earth Day but Earth Week. Masland attended Earth Week seminars at Dickinson College but was not invited to speak.

Just two weeks after the first Earth Day, four protesters were killed at Kent State University in Kent Ohio, prompting Masland to fire off angry letters decrying campus violence, but also to pitch environmental causes. In a letter dated May 15, 1970 to the Carlisle Daily Sentinel, Masland wrote, “If we are to achieve a beautiful land, protect our natural resources and avoid unnecessary pollutants of all sorts, the [environmental] education program has to begin in kindergarten” and continue through college. This letter underscores how highly he valued environmental education, helping to explain why he gifted Kings Gap to the state of Pennsylvania. It’s not clear, however, whether the possibility of an Environmental Center was part of the discussion before the deal was sealed.

“If we are to achieve a beautiful land, protect our natural resources and avoid unnecessary pollutants of all sorts, the [environmental] education program has to begin in kindergarten. . .”

Frank Masland in letter to Carlisle Daily Sentinel, May 15, 1970

Masland the Cold Warrior

By the 1950s, Dickinson college was starting to relax its affiliation with the Methodist church. The professors were also leaning more and more liberal. These changes did not sit well with Masland. He had been a generous benefactor of the college over the years. In 1954 he became vice president of the board of trustees. In the midst of the McCarthy era in 1955, someone testified before the McCarthy committee that a Dickinson assistant professor by the name of Laurent LaVellee had once been a member of the communist party. When LaVellee was called to testify to the committee in 1956, he invoked the fifth amendment more than 50 times. As a result, Dickinson’s president suspended the professor on the grounds of showing disrespect to the committee, pending a hearing by the Dickinson trustees, where Masland carried much influence. The incident sharply divided the Dickinson campus, with many students siding with Lavellee. Although no charges were pressed against Lavellee, the Dickinson trustees voted to terminate his contract anyway. Lavellee appealed, prompting the full board of trustees, chaired by Masland, to meet at Kings Gap in June of 1956. The board once again voted to terminate the professor’s contract, despite there being no evidence of incompetence or any attempts to indoctrinate students. Biographer Smith calls the incident a “shameful chapter” in Masland’s life.

Masland’s legacy

Masland was no doubt a deep thinker when it came to some of the bigger questions. An example of his “out of the box” thinking was his belief that churches should take an active role in preserving natural landscapes, because the church and the national park service shared a mutual interest: the preservation of the human spirit. God may have given man dominion over the earth, but to Masland, that meant stewardship above all else, and a responsibility not to abuse and destroy the earth. Humans need to recognize “the interdependence of all that is a part of God’s creation, that all things hang together and if they don’t, man joins the other endangered species,” said Masland in a 1970 speech, aligning himself with the vanguard of environmental thinking.

Masland was one of a small group of environmental influencers at the time, including Wendel Berry, Edward Abbey, Wallace Stegner, John Saylor, and Rachel Carson. While he worked closely with a few of them and had a passing acquaintance with others, he probably had a much greater impact on policy than most of them, given that he worked closely with Stewart Udall for eight years. To his credit, Masland did not seem to crave public attention. Nor did he publish anything aside from a small number of essays and articles, though he left behind a substantial body of letters and speeches, now available at the Dickinson archives. Today his name is unfamiliar to most people, even in his home state of Pennsylvania, but his legacy still looms large.

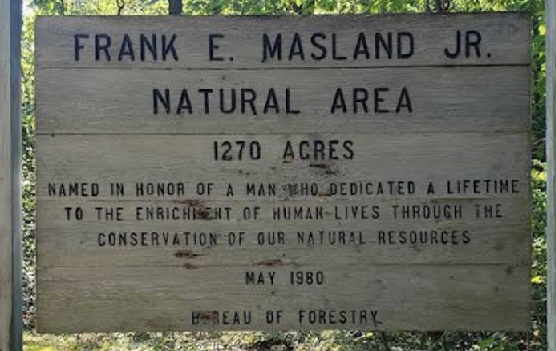

In case you are looking for ways to experience nature as Frank might have intended, there is the Frank E Masland Jr. Natural Area, a 1,270-acre preserve located about 20 miles northwest of Carlise. There is even a primitive campsite for the extra-adventurous.

To learn more about the Maslands, the Masland family website has many historical photos and other information.

References:

Dickinson College Archives and Special Collections have large troves of Frank Masland’s papers.

A Conservative Environmentalist: The Life and Career of Frank Masland Jr., by professor Thomas G. Smith, published by Penn State University Press, 2024

Article on finding the best trails in the Frank Masland Natural Area